A Local Alternative: Access Affordable Healthcare

When the Affordable Care Act, or Obamacare, was signed into law, it may have been one of the most polarizing legislative decisions of 2010. But while the Act might have also had its share of benefits or flaws (depending on whom you ask), its goal of expanding health care access brought insurance of some sort to 16.4 million people previously uninsured, many from smaller businesses that otherwise would not have offered benefits and from those under 26 without the financial means to obtain insurance.

Yet, as of 2016, 28 percent of working-age adults in the U.S. were reportedly underinsured, and nearly half of this group skipped health care they needed due to cost concerns. Because of this, the clinic or hospital is ironically not a place of security and health for the underinsured, but of fear and financial strain.

During any given appointment, the underinsured patient’s thoughts might be less about their ailments themselves and more about how they might pay for them: what will my co-pay be? How long will I have to wait to find out what my high-deductible insurance bill will be? What if my insurance doesn’t cover this expensive prescription I need to survive?

Obamacare has certainly made historic strides in giving a larger population more access to health care, and is therefore celebrated by many, but opponents argue that on the bottom line, the underinsured are still not receiving the health care they need.

This has left people on all sides of the debate in question: how can we bring affordable health care to America?

That’s a question Dr. Thomas Willett set out to discover when he opened a new Green Lake, WI-based independent clinic in 2010, aptly named “Access Affordable Healthcare.” Uniquely, Access does not accept insurance, which Willett says actually saves patients money in the long run.

Access Affordable Healthcare, also known as Green Lake Medical Center, is located on N6205 Busse Drive.

Originally planned as a two-year experiment, Willett says the idea came from his old practice, where he realized 62 percent of operation costs went into back-office operations like billing and insurance filing, a practice which he says ups treatment rates and, as a result, hurts the consumer.

“The insurance costs are going crazy,” Willett says. “Patients aren’t going to go to the doctor until they get really sick.”

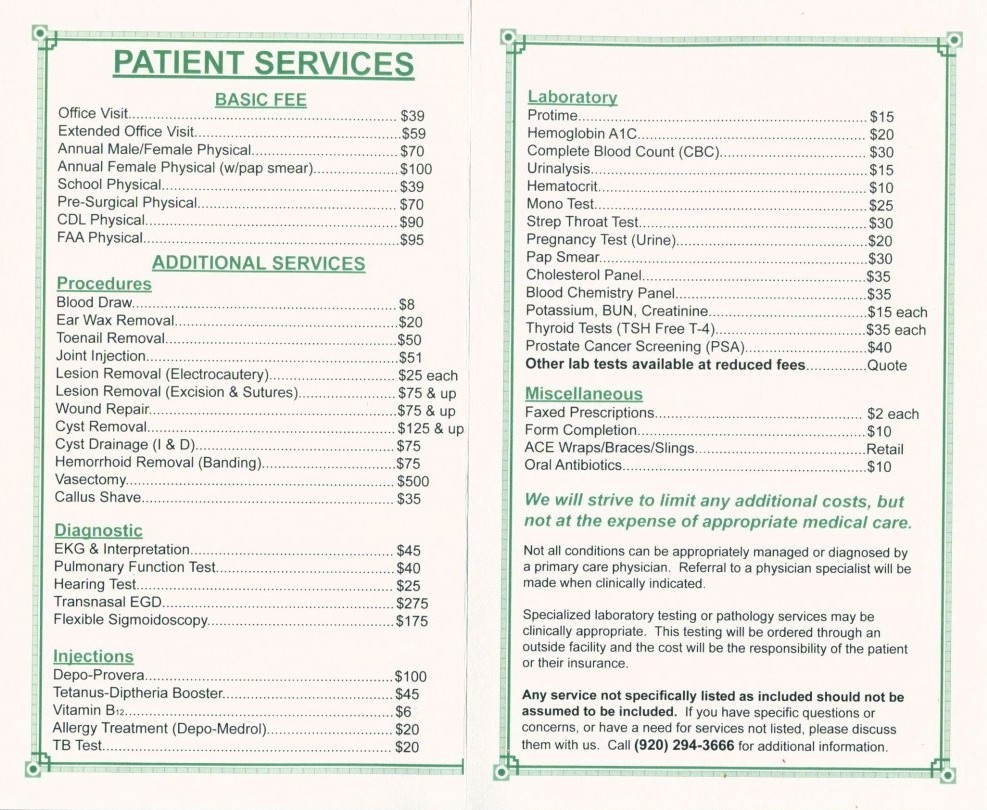

By forgoing insurance, Willett can remove most back-office operations, save 62 cents on the dollar and bring those savings directly to patients. A check-up is only $39, physicals range from $39-100, lab tests and diagnostic procedures are $15-40 and vasectomies are most expensive at $500. Patients are charged up front and not billed after the appointment.

Willett also provides a menu showing all the patient services the clinic provides. Not only does this let patients see the savings firsthand, but it also creates a sense of transparency larger hospitals have had difficulty matching because of the way insurance is filed and due to the variability of insurance policies and their coverages.

“I’d like to get hospitals to make a menu,” Willett says. “You gotta give them something; they just don’t get that.”

He goes on to argue that in some cases, patients might pay for services they may or may not need because they weren’t clear on what procedures are most important or how much they cost.

“If you don’t want to get it all, just do [the most important things],” he says. “There are things to do tests for, but often times you’re just wasting money.”

The combined features of transparency and not having to deal with high deductibles or co-pays make Access Affordable Healthcare an attractive option for those who are underinsured, or even those who simply don’t want to deal with the hassle of insurance.

“There’s such a high deductible if they have insurance — why would they go there?” Willett says. “I have people coming in who have insurance. They just say, I’ll pay you whatever it is.”

Access Affordable Healthcare proves that insurance companies can benefit from the back-office reduction, too. While the clinic generally doesn’t accept insurance, it has an arrangement with Green Lake County and WCA Group Health Trust to insure county employees who go to Access. Willett simply sends a bill to WCA, who then reimburses the clinic. In its most basic definition, insurance is designed to pay fees on behalf of the insured, so Willett says the benefits patients get by saving money at Access is also a benefit for the insurance company.

“Insurance companies like it because they save so much money. The county likes it because it saves them money. The patients like it because they don’t have to pay a co-pay,” Willett says. “So it’s a win-win-win situation. Gets rid of the middleman.”

Willett hopes to show other doctors that an independent, insurance-free practice could be a sustainable model that doesn’t affect their wages, and he hopes that more doctors go this route in the future, experiment more with what works and what doesn’t in this model and even incorporate services Access doesn’t, like surgery.

In fact, he says there’s a group of doctors in Oklahoma City who perform orthopedic surgeries under the same business model. Willett says he’d do the same thing if he weren’t in his mid-70s.

“[Hypothetically], I’d love to turn this into a surgical. I [used to] get paid anywhere from $300-500 to do a surgery, and patients [pay] $4,000-5,000,” Willett says. “They’re doing it for $900-1,000 out in clinics. Those procedures could be done in a clinic like here.”

But according to Willett, there a few lingering problems to this clinic model, some that he has answers for and others that he doesn’t.

One question Willett has pondered is how to bring this type of health care to those on medical assistance like BadgerCare, who might be unable to pay up-front costs and would therefore be forced to spend more money at other hospitals.

In 2012, the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel reported that Willett pitched a modified BadgerCare system to Wisconsin’s legislators to address this issue. Under the proposal, BadgerCare users would have prepaid debit cards they could use to pay medical fees up front.

The plan, which Willett believes would have saved the Green Lake County $550,000 in office visits, didn’t make it past talks due to the difficulties that would arise from enforcing patients to use the sums only for medical payments, as well as having to get permission from the federal government to implement.

“I talked about that at the Capitol, and nothing came of it,” Willett says. “It was really hard for them to understand. How do you control BadgerCare cards? It kind of fell by the wayside, which is too bad.”

Out of the approximately 19,000 Green Lake County residents, Willett says 2,300 are on medical assistance. That’s more than one-fifth of the county’s population who might not even be able to spend the $39 up front for an office visit. Because of this, he believes that before affordable healthcare can be possible under this system, a solution first needs to be found for those enrolled in BadgerCare.

“I really wanted the BadgerCare,” he says. “They don’t have anything to pay with besides [that]. Somehow, that would have to be resolved.”

Another barrier is urgent care centers and emergency rooms, which Willett doesn’t think would work in an insurance-free system.

“It’s not an emergency room if there’s no emergency,” Willett says. “The problem with the emergency room is that you need so much — the overhead is so high because you’ve got to have somebody coming in full-time whether [a patient’s] coming in or not. Somebody’s got to pay for it, and think of all the drugs you would need.”

And if the patient is alone and incapacitated or otherwise unconscious, it’s impossible to pay up front, and even if the patient is technically conscious to pay, there might still be ethical considerations to consider, Willett says.

And if the patient is alone and incapacitated or otherwise unconscious, it’s impossible to pay up front, and even if the patient is technically conscious to pay, there might still be ethical considerations to consider, Willett says.

“In our system, you have to pay cash, but then how are you going to pay cash if they come in and they’ve got a heart attack? ‘Just a minute, sir, before we go out there, I need to get your $500 from you. Is it in your right pocket?’”

Willett hopes that solutions are found for these shortcomings, but he says the more likely route society is going in for affordable health care is through a single-payer, government-funded model, which he says has its own share of pros and cons.

“I think the ultimate thing is socialized medicine will happen,” he says. “All the countries have it. It would be better for equality.”

But he says the downfall is that any costs saved by government-funded health insurance would be offset by taxes. For instance, under former presidential candidate Bernie Sanders’ “Medicare for All” plan, income deductions would come in the form of a 6.2 percent payroll deduction, a 2.2 percent standard income tax and a a 37-52 percent income tax for high earners, to name a few. Depending on which income bracket the taxpayer is in, taxes could range from somewhat small to astronomical, but the overall tax rate of Sanders’ plan is no doubt much higher than that of a conservative budget plan.

“The problem is, it’s going to be very expensive,” Willett says. “[Taxes are] going to go up astronomically.”

Willett is also concerned that without monetary incentive and the same type of competition, doctors might become less motivated to research advancements in medicine, be it prescription drugs or curing diseases, which would slow down overall productivity and advancement.

“If you have a socialist system and you’re a doctor, you have to go eight hours, then 4:30 comes, and you close the doors,” he says. “You earn money by [competing with people]. Otherwise, you’ll become lazy. The incentives are gone.”

Willett also says the downside of free-market incentives is the rapid inflation of prescription drug prices where, according to CNN, 20 common prescription drugs have inflated 10 times faster than the annual inflation rate. Nitrostat, a chest pain medication, for instance, has increased in price by 477 percent since 2012.

“The cost of medicine is skyrocketing, and there’s no clamps on it. The greed is just sad,” Willett says. “So you’ve got the good and the bad. You need to get incentives to get things done. In medicine, it’s tough — is it a privilege or right? And maybe medicine should be treated better.”

Willett says he hopes to see advancements in insurance-free clinic systems like Access, but in terms of its current operations, he says the system is sustainable and viable. After the two-year experiment phase ended, Willett decided to keep the clinic going due to its success. In its first year, Willett treated about 70 patients per month, and now he sees about 22 patients per day. The original goal was 20.

For more information about the clinic’s services, call 920-294-366 or email [email protected]. Access Affordable Healthcare is located at N6205 Busse Drive in Green Lake, WI and is open from 8 a.m.-5 p.m. on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays.

Leave a Comment