Football coach takes his message beyond the field

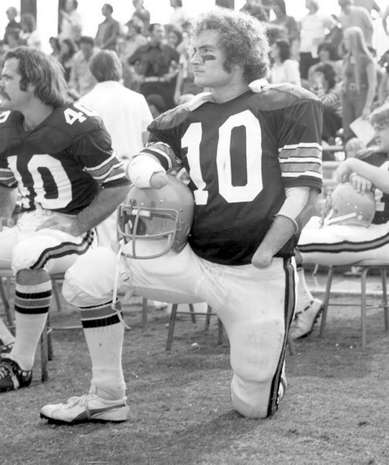

Mark Speckman doesn’t let barriers block him. Instead, after being born without hands, he learned to adapt to the world that surrounded him.

“I think people like a good story. … We haven’t really come that far from kindergarden. People like sitting on the rug and hearing a good story,” says Speckman who is the author of “Figure It Out: How I Learned to Live in a Digital World Without Digits.” He is also the assistant football coach and offensive coordinator for Lawrence University since May 2015.

Speckman will speak tonight during a fundraiser for the Fox Cities Book Festival. He compiled his book with a former player, but wrote the forward and last chapter himself. The book was published in 2012 and is in its second edition. Speckman also has earned the title of inspirational speaker since 1996 when he began taking on a variety of engagements including the likes of Nike, Boeing and Nationwide Insurance to name a few.

Tickets for tonight’s fundraiser at Riverview Gardens in Appleton will be available at the door for $25. Doors will open at 6:30 p.m. and attendees are invited to enjoy live music and a cash bar. Speckman’s talk begins at 7 p.m. with a question-and-answer period to follow. His book will be available for purchase as well.

Speckman became involved with the book festival after a chance encounter between his wife, Sue, and the husband of Ruth Bloedow. Bloedow is the co-chair of the Fox Cities Book Festival with Kris Clouthier. She struck up a friendship with Sue and later discovered her husband had written a book, which Bloedow asked to see a copy of. “I was thinking it was all about football,” she says, but quickly realized she was wrong.

“He’s a great storyteller. The information just flows out of him,” shares Bloedow. “They are the most interesting and positive people I have met in a long time.”

Although, he doesn’t aim to glorify himself, Speckman says he is grateful to have been able to share moments with those who resonate with his message.

Speckman, the second child of four, credits his parents and good mentors for encouraging him to figure out solutions to everyday situations. He has an older brother, and a younger brother and sister who were born with hands. Today, Speckman also is the father of Tim and has two stepdaughters, Lisa and Julie.

Speckman, the second child of four, credits his parents and good mentors for encouraging him to figure out solutions to everyday situations. He has an older brother, and a younger brother and sister who were born with hands. Today, Speckman also is the father of Tim and has two stepdaughters, Lisa and Julie.

“The best thing they did was make me do what everybody else did,” Speckman says of his parents as he recalled learning how to sweep with a broom or pick up an instrument he could figure out how to play. Through it all, Speckman’s parents never babied him, nor did they make the loss of his hands an issue.

At the age of 11 months, Speckman was the third youngest person in the United States to be fitted for hooks, he says. His parents only rule was that he needed to wear them in public, but Speckman never took to them. Most days, he wore them to school as his parents asked, but took them off upon his arrival and put them back on before heading home.

“I do way better without them,” he says, adding that by freshman year of high school he stopped using them altogether.

His mother’s only advice before heading off to college was that he didn’t attempt to climb any mountains. Instead, Speckman went against her wishes and enrolled himself in a ropes class.

“I’m constantly figuring it out, whatever the situation is,” Speckman shares, noting that he has to figure out things like putting change into a parking meter. “I think we all have it, I just use my radar more than anybody else does.”

He began playing football in the sixth grade because “nobody ever told me I couldn’t play, so I did,” he shares. Speckman stuck with football through high school and later college, before coaching.

He began playing football in the sixth grade because “nobody ever told me I couldn’t play, so I did,” he shares. Speckman stuck with football through high school and later college, before coaching.

“I had all these ideas of what I wanted to do, but I wondered what would get me through the fastest,” he says.

Initially, Speckman tried special eduction before determining that wasn’t for him and went on to teach social studies and U.S. History, along with coaching anything he could including football, track, baseball, soccer and football.

“I always felt like I was doing two full-time jobs,” shares Speckman who has been coaching for 38 years between high schools, at the college level, including Willamette University, and professionally coaching the Montreal Alouettes of the Canadian Football League. He is highly regarded for his knowledge of the “Fly” offense.

“I think good coaches have to love the X’s and O’s part. You have to keep grooming,” Speckman says of the students he’s worked with. “It’s a fascinating chess game.”

While Speckman loves the competition aspect of football, he also believes a program done right is valuable for other reasons from mentoring to teaching to discipline to doing a job — and doing it right — and pushing students in a positive direction, along with creating strong bonds that never lapse.

While Speckman loves the competition aspect of football, he also believes a program done right is valuable for other reasons from mentoring to teaching to discipline to doing a job — and doing it right — and pushing students in a positive direction, along with creating strong bonds that never lapse.

“You’re pushing somebody to be better than they probably would be on their own,” Speckman notes. He also enjoys the connection he develops with his players. Speckman recently talked to a former player who is now coaching and picked up like there was never a pause in their contact.

“That’s the fun thing about high school, they come in as skinny, little freshmen and leave as young men,” he explains.

As Speckman shares, it’s the “tough things that shape you.” Whether physical, mental or spiritual, he hopes that people will realize it’s possible to see things differently through his talk at the Fox Cities Book Festival fundraiser.

Speckman jokes that he has a box full of football notes that he could turn into another read, but he’s unsure if that will happen in the future.

“Maybe I’ll write it someday. I keep saying that. I probably won’t, but I keep saying that,” he says.

Leave a Comment