Shock Value

Contentious art can spur worthwhile conversations

When Natalie Halvorsen scheduled a meeting with a friend and creative collaborator in early June, she suggested they meet at the coffee shop four blocks from her home in Green Bay’s Olde Main Street arts district. Halvorsen, an artist and art educator, had hung a display of her monoprints and paintings there less than a week earlier, so it made a fitting backdrop for scheming up new projects.

“As we were leaving, I noticed one of the pieces was missing,” Halvorsen says. “I asked the baristas if they knew what happened to my artwork. They got really quiet and looked at each other, and I knew something was wrong.”

The show was scheduled to be on display through July, however, an employee informed Halvorsen that several customers had complained about one particular piece, a depiction of the Blessed Virgin. According to Halvorsen, the piece was taken off the wall and stored in a locked closet for six days without her being notified.

“That’s what hurt the most, that it was locked away,” she says. “I was made to feel like I [did] something really blasphemous.”

Fear No Art

The irony, according to Halvorsen, is that she encourages her own students to avoid self-censoring out of fear, shame or guilt. When she followed her own advice, it led to the very feelings she wanted her students to challenge.

“I always tell my students, ‘Fear no art,’” Halvorsen says. “We shouldn’t feel bad or ashamed of a creation no matter what it is.”

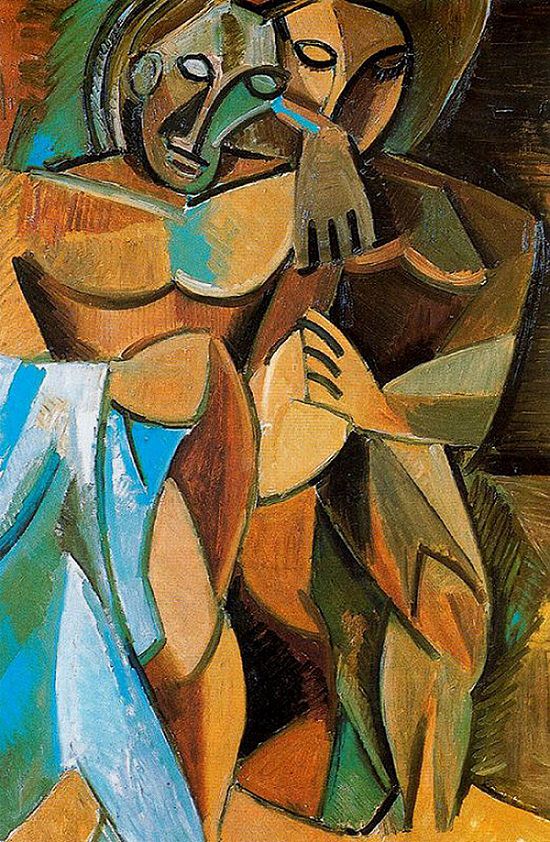

Spanish artist Pablo Picasso (1881-1973) painted “Friendship” in 1908. The work depicts two androgynous figures in an embrace and has been interpreted as an image of both lesbian and heterosexual love.

The offending piece of Halvorsen’s work, titled “Wunderkammer Mary,” was a concept drawing that depicts a Madonna as a centaur, a mythological creature with the upper body of a human and the lower body of a horse. From the waist up, the figure is a classic Madonna in a traditional Christian iconography style – minus the unicorn horn jutting from her forehead. From the waist down, the Virgin Mary has the body and legs of a horse.

Halvorsen describes the piece as pop surrealism, an art style characterized by the use of cultural icons to make a social statement.

“My intention was to depict the Virgin Mary in a wondrous, fantastical way which reminds me of Walt Disney’s ‘Fantasia,’” she says. “Ever since I was a little girl I’ve been enamored with it, so for me I was having an innocent moment rendering this character.”

Some coffee shop patrons didn’t see it that way. This may not be surprising in a city where 65 percent of residents identify as Catholic, according to a 2010 Association of Religious Data Archives report. Critics viewed the piece as mocking of Catholicism and disrespectful to one of the religion’s most revered figures. The coffeeshop owner declined to comment for this story.

While the definition of what constitutes offensive art is individual to each person, it can also reflect the majority consensus of a community. In his book “Not Here, Not Now, Not That! Protest over Art and Culture in America,” Dean of the Herberger Institute for Design and the Arts at Arizona State University Steven Tepper writes that protests to art “represent the democratic outcome of citizens negotiating the consequences of social change within their communities.”

If this is true, the Fox Cities is undergoing a revolution. It’s not a fact that can be accurately quantified by multiplying the number of creative job opportunities by how many arts venues exist in the region and dividing it by the number of art schools. Rather, it can be seen and felt in the kind of work local artists create and the reactions it gets from the community. Perhaps the implications of such art and critical responses indicate that the work is bolder in the first place or that the community is grappling with its ideals and determining its place in the broader art world.

“These are just the beautiful growing pains of becoming a cool place to have art.” – Beth Zinsli, Wriston Art Center Galleries director and curator

Either way, the questions raised and the conversations started in these situations seem necessary for a fledgling art community. Beth Zinsli, director and curator of Wriston Art Center Galleries at Lawrence University in Appleton, views all reactions to art, both enthusiastic and critical, as a sign of growth.

“If people chose to put blinders on and not respond to art, that wouldn’t be good,” Zinsli says. “The fact that people want to say something about art means it’s doing its job.”

Art that generates the most critical responses generally depicts either religious, political or sexual content. This is true today as well as from a historical perspective. For example, “The Last Judgment,” a fresco by Italian Renaissance painter Michelangelo at the Sistine Chapel in Vatican City, caused controversy with its depictions of unclothed human souls at the second coming of Christ. Pablo Picasso’s “Guernica,” which depicts violence that ensued during the Spanish Civil War, has a long history of inciting political debate over warfare and activism.

As a society evolves, so does its definition of offensive material. Content and themes that were commonplace may now be outdated according to contemporary values. Sometimes the opposite is true. What was once scandalous may be acceptable, and even celebrated, by today’s standards. Zinsli says keeping history in the rearview mirror helps puts things into perspective today.

“What we now hold up as the canon of art history was in a lot of cases the things that were initially rejected from academic salons,” she says.

Great Expectations

In recent years, the Fox Cities have been introduced to pop up art shows – temporary exhibitions that often occur in nontraditional venues such as empty storefronts and retail spaces. Pop up shows can last a month, a week or one night.

These short-run exhibitions contribute to a rich and diverse art scene by allowing emerging or local artists to share their work with audiences who might not have the chance to see it otherwise. The brevity of pop up galleries also ensures that energy and attendance remain high rather than petering out over the course of a long exhibition run. Pop ups can also present challenges. Unlike an established gallery space, the expectations can be unclear for viewers in venues that don’t typically display art.

Hortonville-based art curator Kate Mothes has been organizing pop up galleries since 2015 through Young Space, her blog and nomadic art platform focusing on early career contemporary artists. She’s utilized empty storefronts, vacant suites in office buildings and art co-ops.

If a show’s venue is also an operating business, its primary function can dictate what viewers expect to see and influence the way art is interpreted. The case of Halvorsen’s “Wunderkammer Mary” is a perfect example, Mothes says.

“If you’re walking into a coffee shop or restaurant, you’re not necessarily expecting to see religious or political artwork,” she says. “But if that same piece had been in The Trout Museum of Art as part of a show, it wouldn’t have gotten quite the same reaction.”

University of Wisconsin-Green Bay Professors Alison Gates and Daniel Meinhardt learned the value of setting expectations within a venue while exhibiting their collaborative mixed-media art piece titled “Gender Reveal Party.” The piece integrates original medical illustrations by Meinhardt, associate professor of human biology, with baby clothing dyed by Gates, chair and associate professor of art and women and gender studies.

The piece is comprised of five baby onesies hung on a clothesline. One is solid pink, one is solid blue and three in the middle are tie-dyed in combinations of the two colors. Applied to the snap-down flap of each onesie is an illustration of a distinct stage of the Prader scale, a rating system for the measurement of the degree of virilization of human genitalia. The piece was intended to challenge society’s binary view on biological sex.

The work displayed uncontested at dedicated art venues such as The ARTgarage in Green Bay and as part of Lawrence University’s Rabbit pop-up gallery in Appleton. But when it showed at 100Arts in Madison, an art gallery within a lobby of a coworking space, it received some negative attention.

“Basically, people bringing their clients in weren’t prepared to answer questions about it,” Meinhardt says.

As a result, 100Arts hosted a facilitator-led discussion for all parties to voice their viewpoints. Meinhardt estimates about 100 people attended.

“It turned out really positive,” Meinhardt says. “At the end, the people who had objected to the piece seemed to say that if we had simply [had this discussion] in the first place and they would have had some information and understood it, they wouldn’t have had a problem.”

Ultimately the piece was removed, but only shortly before what would have been the scheduled conclusion of the exhibition. Gates says the conversation that the piece generated made it successful.

“It was exactly what we could have hoped for as educators. I think one of the many functions of art is to repackage information to make it available to a new audience,” she says. “If it makes for an open dialogue about something people normally wouldn’t talk about, then that’s the silver lining.”

Educating Art Consumers

Art that contains challenging subject matter can cause, well, challenges. Many curators agree that along with setting the expectation for the style and subject of work that will be displayed in a particular venue, providing background information to viewers about individual pieces is key.

“It’s hard to put a work of art on the wall and expect everyone to be able to appreciate it in the same way,” Zinsli says. “There is a little foregrounding knowledge that needs to be there, whether that work is done by the curator, the artist or institution, it needs to be there.”

Zinsli says art should serve as a valuable two-way conversation between the creator and the consumer. This could be in the form of a posted artist statement or a talk given by the artist.

“In both large and local cases, when these kinds of issues come up, the dialogue might not be shared with the audience,” Zinsli says. “If the dialogue is just between the curator and the artist, the audience is left out of the conversation and that’s where misunderstandings can come up.”

This is true for all art forms, including the performing arts. Maria Van Laanen, executive director of the Fox Cities Performing Arts Center in Appleton, says it’s rare that a performance doesn’t solicit at least one phone call from a concerned patron.

“It is shocking to me when we don’t hear anything,” Van Laanen says. “I actually worry the other way then. Was the community moved by [the performance]? Was it a poignant message? Did anybody even care?”

As with visual art shows, properly preparing audiences ahead of a performance can help mitigate some concerns. Van Laanen explains that the Center offers preshow discussions, family activities and interactive workshops tied to many performances so expectations are clear before the curtain raises and audience members have an opportunity to share their viewpoints.

Think of it this way: would you buy a vacuum, select a vacation destination or hire a handyman without conducting research first? If the answer is no, consider applying the same consumer research to art, Van Laanen advises.

“Not every show or work of art is for everybody and quite frankly it shouldn’t be,” she says. “As a community member, you have the opportunity to educate yourself in advance and make a choice for yourself.”

This is an easier task with ticketed shows than casually encountered coffee shop art, but both scenarios present viewers with a choice.

“If you don’t agree with something fine, don’t engage or don’t attend, or challenge yourself to engage and learn even more,” Van Laanen continues. “I think that idea of challenging your own preconceived notions gives everyone a chance to grow and learn, and that’s really exciting.”

One of the main goals of the Center, Van Laanen says, is to present art forms that reflect different facets of the Fox Cities and the world around it. Some performances touch on topics like racism, identity and political issues.

“The arts provide a way that’s less combative to explore some of these topics,” Van Laanen says. “When you can enter into those dialogues through the arts it gives you a chance to maybe gain more empathy along the way.”

Whether the topics are being broached by a Broadway play or a painting by a local artist, the Fox Cities are wading their way through serious questions and deciding what true support of the arts looks like in our community.

“What’s beautiful about what’s happening right now, is there are people putting art out there and pushing boundaries,” Zinsli says. “Landscapes and [still life paintings] are awesome, but is there a way to have art that pushes boundaries a little without causing us to rupture?”

Zinsli believes the answer is yes.

“These are just the beautiful growing pains of becoming a cool place to have art,” she says.

Leave a Comment